We’ve come a long way since the early days of email and its critical role in all corners of the internet. Today, email is the life line between brands and consumers — transactional email helps close the loop on user-initiated transactions, thus limiting the amount of time both parties need to spend tying up loose ends. Password resets have automated the most basic customer service function. Believe it or not, there used to be long wait times on phones to change a password or re-access an application that locked you out. According to Forrester research, a helpdesk call for a password reset can run a company $70 per call!

Meanwhile, two-factor authentication that combines mobile apps, PII designated by the user and, on occasion, an email have made critical applications and services more secure. Email is not only the means by which the internet has been built — allowing collaboration between remote parties — but it has become the very foundation of digital identity, in addition to the most reliable, personalized and universal document store in the world.

Read part 1 of this series: Email’s humble beginnings and the birth of tracking pixels

The rise of spam

At the same time that the commercial use of the internet became more than just an idea (Amazon was launched in 1994), the potential exploits of email became equally obvious as more and more people began to use the medium.

The genius of email was that it was essentially an open platform and standard when it was built. There was no such thing as authentication because the concept of trusting the sender of a message was a given due to email’s academic originators and user base. The progenitors of email couldn’t have imagined the prolific use of the medium today — the sheer scale and velocity of email communications is mind-blowing. But this openness and scale are precisely what drew fraudsters and cyber criminals to abuse the channel.

The term spam was coined in 1993 — not in reference to email but in relation to messages posted to USENET, quite accidentally at first, but then maliciously. Soon this term was applied to all forms of Unwanted Commercial Email (UCE). By the late 90s, email spam was a massive problem and several different approaches were used to try and curtail its growing volume. Companies like MAPS were born to identify and list spam sources (IPs and mail servers) generating millions of unwanted messages. Software such as SpamAssassin was released in 2001 as an off-the-shelf set of filters capable of identifying spam sent to a receiving domain. ISPs and mailbox providers began keeping tabs of IPs sending massive amounts of spam as a means to identify and stop them at their source, however temporarily.

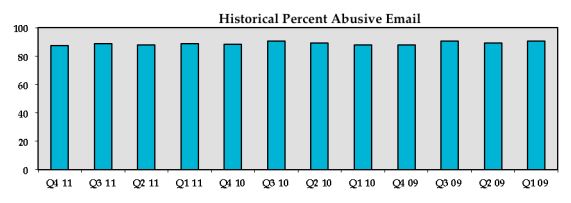

As you can imagine, these measures helped but the onslaught continued mostly without cessation to this day. It was estimated that nine out of every ten messages back then was spam. This metric is more or less unchanged today. Some measures, like Cisco’s Talos, put the ratio at 85 percent spam to 15 percent legitimate email; others say that legitimate email makes up less than 10 percent of total global email volume. Whatever the actual number is, there’s a lopsided affair with spammers sending more mail than legitimate marketers.

Image Source: Messaging Malware Mobile Anti-Abuse Working Group’s Metric Reports

With the rise of spam, new technologies and methods for dealing with it became important and essential on the internet. First, the U.S. Congress tried their hand at it by passing the CAN-SPAM act of 2003. This put some teeth around mail abuse but didn’t have the deleterious effect anti-spam advocates and crusaders were hoping for. AOL pioneered technology to give users the ability to identify and report spam in the form of the “spam button” around the same time. This, as we know, has been ubiquitous in just about every email client on the planet ever since.

The birth of the spam button was, at least in part, due to how spammers abused and subverted the legitimate use of unsubscribe buttons. Before CAN-SPAM, the unsubscribe link wasn’t a staple of every legitimate email. However, both spam and legitimate senders used the functionality and over time recipients realized that clicking an unsubscribe link didn’t always deliver the desired result. When the link couldn’t be trusted, it simply alerted a spammer that the recipient of that email was indeed a live person. Spammers launching dictionary attacks would include unsubscribe links as a means to determine if the randomly generated recipient existed and to help present their messages as legitimate.

It’s taken many years, but the unsubscribe link has become trusted once again. Not only has it become trusted, but mailbox providers are also actively using the list header to create an unsubscribe function at the top of an email. Pro tip: Don’t bury your unsubscribe link. Recipients have multiple ways of opting out of receiving communications; allowing them to unsubscribe is by far cleaner and less detrimental to your overall sending reputation. By obfuscating it in footer text and making it hard to find, you’re compelling them to mark your message as junk, or even worse, a phish out of sheer frustration.

A new framework is born

Around 2004, the final specification for SPF (Sender Policy Framework) was released, creating the beginning of a trust concept between the senders and receivers of email. SPF creates the ability to authorize, through a DNS record, an IP to send on behalf of a domain. SPF was a good start, but spammers to this day publish SPF records because it wasn’t a bulletproof solution to the growing volume of spam. Receiving domains could make more informed decisions about the origins of a given message, but it wasn’t a panacea to the problem.

At the same time SPF was being published, a second standard was in the works: DKIM (DomainKeys Identified Mail), which was a cryptographic solution for ensuring that content wasn’t tampered with during message transport. Creating standards around where a message originates and what’s in the message when it’s received versus when it was sent greatly help with establishing the trustworthiness of a given email and the sender that’s sending it. But again, this was not a total and complete solution to the global epidemic of spam.

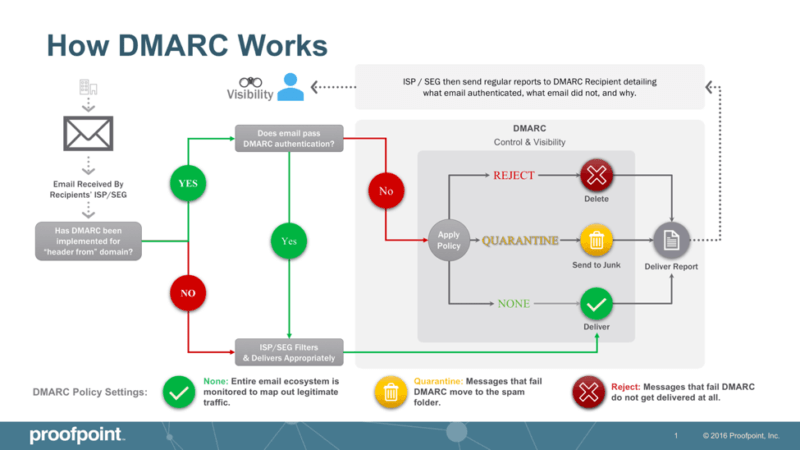

DKIM, along with SPF, became the foundation for DMARC (Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance) in 2011. DMARC allows the sender of an email to create a set of instructions for the receiving domain on what to do if the message fails an SPF or DKIM check. This policy makes it very difficult to spoof brands and deliver fraudulent messages to unsuspecting recipients, or hijack pieces of content to fool filters. If a message fails one or both, the DMARC record can tell the receiving domain to discard the message and not deliver it. Additionally, DMARC forensic reports sent back to the originators of messages have helped them identify where they are being spoofed from geographically, creating greater awareness of the vulnerabilities brands face in the marketplace.

Ultimately, you don’t need to sign SPF, DKIM or DMARC to deliver legitimate email — no mailbox provider explicitly blocks mail that lacks these three mechanisms. However, the goal of all legitimate marketing is to differentiate itself from that of spam. By leveraging these three key technologies to establish the identity and trustworthiness of the sender, you are doing your part in protecting the people that matter most – your customer.

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and not necessarily Marketing Land. Staff authors are listed here.